Questo sito web utilizza i cookie per potervi offrire la migliore esperienza d'uso possibile. Le informazioni contenute nei cookie vengono memorizzate nel browser dell'utente e svolgono funzioni quali il riconoscimento dell'utente quando torna sul nostro sito web e l'aiuto al nostro team per capire quali sezioni del sito web sono più interessanti e utili per l'utente.

Cruise 2022

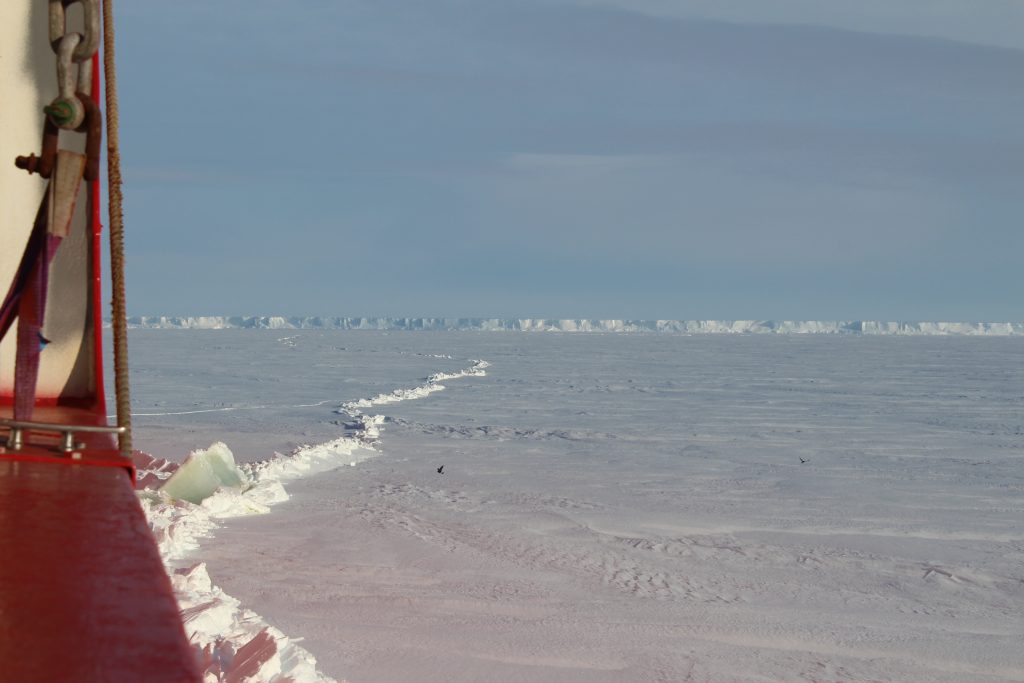

As far as our eyes reach, there is nothing else to see than the dark blue of the water and the sky, blended with different shades of white. We are in the Southern Ocean, standing on the deck of the S.A. Agulhas II, watching birds flying by and the ship breaking its way through the thick sea ice. On the horizon, a wall of pure ice appears. This is the edge of Antarctica, where the Southern Ocean ends and the white continent starts. Watching this beautiful and untouched landscape makes us forget about the four weeks of quarantine we spent in a hotel room in Cape Town before embarking on the ship on the 1st of January 2022. At the same time, our surroundings remind us of the importance of this expedition which is part of “SO-CHIC”, a large EU-project about the Southern Ocean’s heat and carbon uptake led by the French oceanographer Jean-Baptiste Sallée Oceanographer at the LOCEAN laboratory in Paris.

The SO-CHIC project cruise team

An expedition to the heart of the Southern Ocean

When talking about climate change, we typically think about the increase in air temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events that cover the news all over the globe. But that is actually only one small piece of a complex puzzle. We need to look beneath the ocean surface to understand the impact of increased carbon emissions due to human activities. The Southern Ocean is the main regulator of the excess heat and carbon in the atmosphere. It plays a disproportionately large role compared to other oceans around the world, storing up to 75% of all heat and up to 50% of all carbon. And yet, most of the Southern Ocean remains unobserved, leaving behind a large knowledge gap about the processes linked to heat and carbon exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean. The lack of observations increases the challenge of capturing the complex climate system with numerical climate models. These models are used to simulate future responses to climate change, but outcomes are constrained by the limited amount of existing observations. Thus, projecting changes in the Southern Ocean is among the most challenging tasks for climate models.

The goal of our expedition is to collect observations from a key region of the Southern Ocean that has an increased exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean, a so-called polynya region. Polynyas are large openings in the sea ice that expose the ocean to the atmosphere. Such an opening in the sea ice has occurred in certain years above the underwater mountain Maud Rise. During our expedition, we sailed to this largely unexplored area off the Antarctic coast to take measurements directly from the ship and to deploy instruments in the ocean that continue measuring ocean and atmospheric properties over several months and years.

A long-lasting quarantine

Room in Cape Town hotel

We were 11 scientists, engineers and flight crew confined to our hotel rooms in Cape Town for two weeks of quarantine before embarking the S.A. Agulhas II in Antarctica. Due to Covid, the cruise had already been postponed by one year. Only huge administrative efforts and international collaborations have made it possible to organize this alternative cruise to the Southern Ocean one year later. In the meanwhile, scientists of the project used climate models to simulate the unobserved areas of the ocean that are to be explored during the expedition. These computer simulations are based on observations in order to provide more realistic results and the modelers were therefore excited about the cruise to go ahead. After deciding what measurements were needed, scientists and engineers worked together to prepare the instruments and calibrate the sensors to ensure a high quality of data.

Once the two weeks of total isolation had passed, we couldn’t wait to fly to Antarctica. But then we received a disappointing text message: Strong storms over Antarctica did not allow any landing on the continent… This meant an extension of the quarantine until the storms had ceased and until the ship—already at the coast of Antarctica—had managed to break its way through thick sea ice that the strong winds had pushed towards the coast. Suddenly, we found ourselves celebrating Christmas alone in our hotel rooms, while negotiations were made to ensure logistics and science could both go ahead as planned.

Finally, we met on the last day of 2021 at the Cape Town airport, ready to take off for Antarctica to collect measurements in this unexplored area of the polynya. Excited to arrive on the ship, we were hopeful that 2022 would be the year for an extensive collection of interesting data.

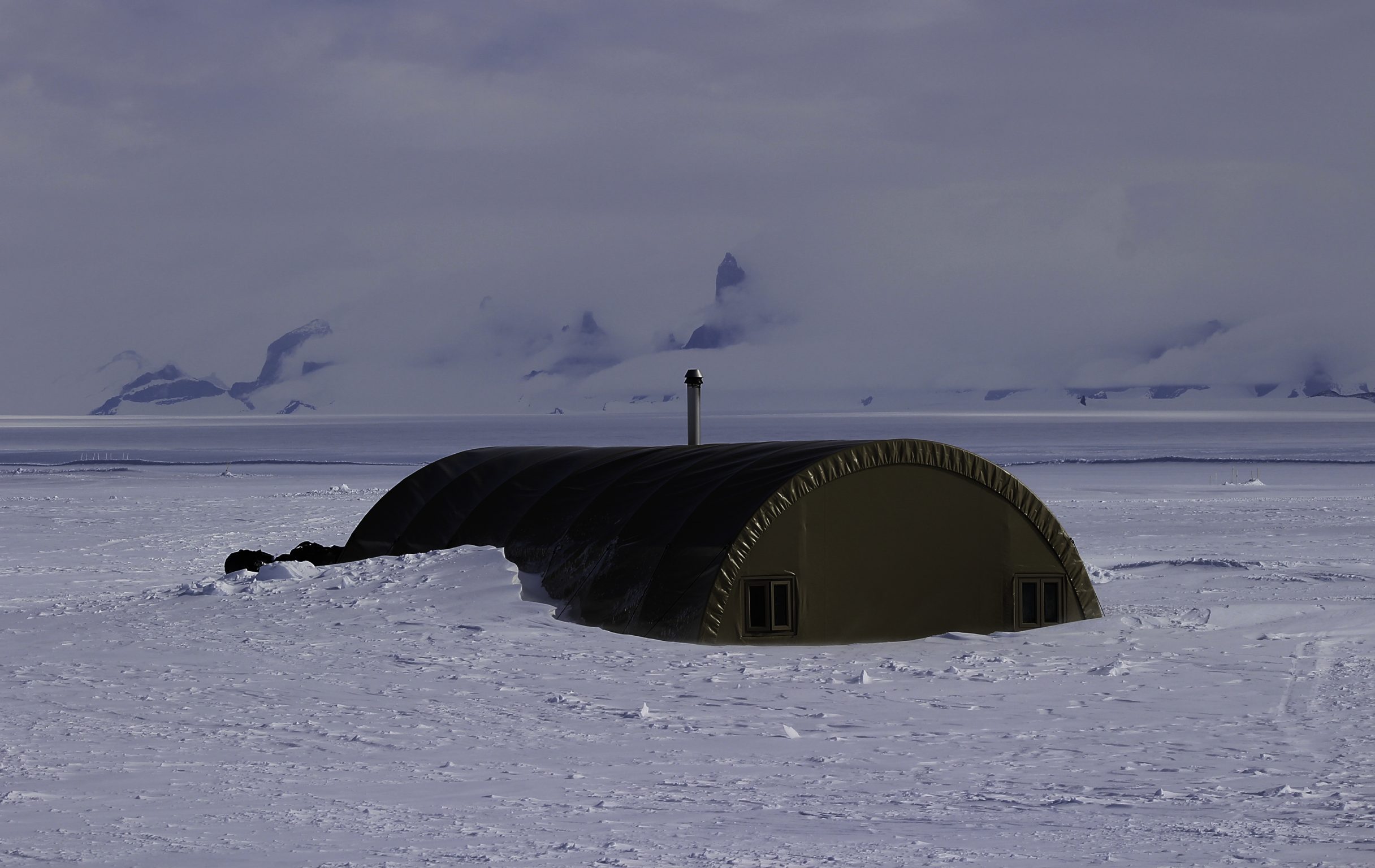

An unexpected journey through Antarctica

Antarctica is a very special and beautiful continent. The trip to the ship was unreal and made us realize the remoteness of the continent. Two weeks of delay due to extreme weather conditions is not an exception for trips to Antarctica. Our plane brought us to Wolf’s Fang, a tourist camp surrounded by stunning mountains and endless white, where we spent 8 hours before continuing taking another short flight to the South African Antarctic research station SANAE. We just arrived in time for the countdown into the New Year together with the overwintering team of the research base. We only got a glimpse of their life in pure solitude, before our journey continued to the edge of the ice shelf where we finally embarked the S.A. Agulhas II.

After the delays, all the uncertainties regarding the cruise, and 28h of travelling through Antarctica, we were utterly relieved to finally see the ship docked to the ice shelf, ready to welcome us. We were excited to start working and went straight into preparing the laboratories and all the instruments that we were going to deploy in the Southern Ocean. We were glad to get some time to familiarize ourselves with the facilities, while SANAE was prepared for the next overwintering team.

The ship Agulhas II moored to the ice pack

Measuring the ocean

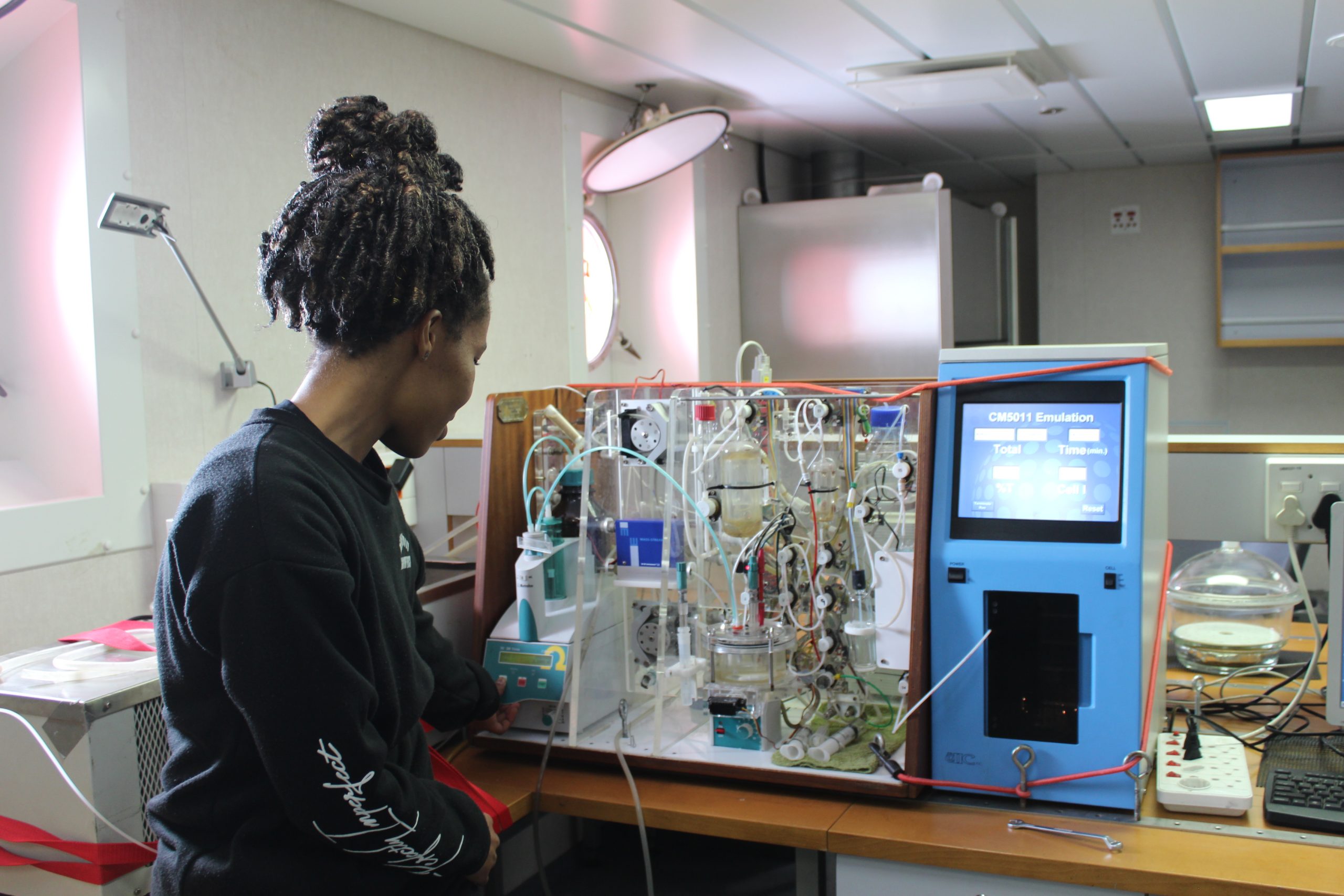

What exactly did we do on the ship besides watching the ship cutting through the sea ice and clumsy penguins sliding on the ice? Once we reached our study site over the underwater mountain Maud Rise, we all had to work hard during the day and night to collect as much high-quality data as possible.

One of the main tasks was to conduct CTD (conductivity-temperature-depth) - measurements that provide information on the salinity, temperature, oxygen and primary productivity throughout the whole water column. These profiles are taken in short distance from each other to provide knowledge on the ocean properties along a transect through areas of interest, in our case across the slopes of Maud Rise.

While these measurements are only taken at one point in time, we were also able to deploy various autonomous instruments in the ocean that were being left behind to record ocean properties over a longer time period.

One example of such instruments are gliders. They are small autonomous vehicles that are controlled remotely to follow specific patterns over months. They are programmed to dive from the surface to about 1000m depth and back to the surface again, where communication happens. Another autonomous instrument we deployed was an uncrewed surface vehicle. This instrument samples in synergy with the diving glider, taking measurements of the surface ocean and atmospheric conditions above the glider. Other instruments that we use to collect measurements drift with the ocean currents either floating at the surface (drifters) or diving at different depths (Argo floats). In addition, we deployed instruments that are anchored to the ocean floor and thus stay at the same location over several months or years.

Preparation of measuring instruments

The different instruments mainly measure temperature and salinity, but also ocean currents, the amount of carbon and oxygen, primary production, sea ice thickness, and fluxes to the atmosphere. One strength of these observations is to combine all their data to understand this region in a new way. This means that our exciting work just starts when we get off the ship. The data will continue rolling in and the different pieces of the puzzle will be put together step by step.

Revealing the secrets of the Southern Ocean

After our intensive work over the Maud Rise area, it was time to pick up the last overwinterers from the South African research station and head back north to Cape Town. We used the transit time across the Southern Ocean to gather all the collected data, to have a first look at the measurements, and to write a cruise report that will serve as a user manual for anyone interested in working with the data. These observations form the basis for future studies within the SO-CHIC project, as they quantify the heat and carbon exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean in the sea ice-covered Southern Ocean. The expedition was a great success since it will considerably extend the network of observational data. In combination with historical observations, the time series taken by the deployed instruments will provide an insight into changes in carbon and heat uptake over time and the processes behind these changes.

Additionally, the data will help to validate computer models that try to reproduce the occurrence of the polynya within the sea ice. These models help to better understand why a polynya occurs and how it impacts the storage of heat and carbon in the Southern Ocean. The observations combined with the models will reveal some of the secrets of the Southern Ocean that are hidden beneath the surface and covered by sea ice during most of the year.

“It is striking that it is only relatively recently that field observations of this remote part of the planet have been established, because of the impressive challenges in getting and working there. At a time where the cruise that followed our expedition on the icebreaker Agulhas II is bringing home groundbreaking images of the wreck of Shackleton’s ship, one the early explorer of the Southern Ocean, we are reminded of the challenges to explore this region of the world, and of the incommensurate risks taken by our ancestors to start exploring and observing this region of the world. Our cruise has humbly continued the early efforts to reveal Southern Ocean mysteries, and slowly pursued to uncover the large parts of this ocean that still today remain unexplored, some almost unreachable.” J.-B. Sallée

Nadine Steiger, a post-doctoral fellow at the Oceanography and Climate Laboratory, took part in the Antarctic campaign. Through her travel diary, this German-born specialist in physical oceanography takes us through the major stages of this journey to the ends of the earth. stages of this journey to the ends of the earth.